History buffs bridge minority gap with new course offering

For the past six months, senior Josh Ogunsaya has been rallying for an honors African-American history class. Ogunsaya, a varsity wrestler and history buff, said unfortunately he has grown accustomed to being one of the handful of black students in his Advanced Placement (AP) classes.

His proposal came about last spring in civics teacher Toni Biasiello’s classroom — though it had really originated sophomore year, when Ogunsaya attended an OPRF meeting for minority AP students to discuss the achievement gap.

This is when he began to wonder why there weren’t African or African-American AP classes. Ogunsaya felt that underrepresented students were more likely to engage in curriculums they felt included by. “Students need to understand their mistreatment and see their accomplishments,” he said. This exact theory was mirrored when Ogunsaya nearly registered for AP European History — then realized that his interest level didn’t match the workload. When Biasiello assigned him the requisite service learning project, Ogunsaya knew what he’d do.

He wrote the College Board urging curriculum expansion. This letter proposed the addition of AP African, African-American, and Latin-American history courses, and the diversification of current language offerings. Hindi, for example, is the world’s fourth most-spoken language and Italian is the 22nd — yet only one has a sanctioned curriculum. Ogunsaya sent the letter in late May. He is still awaiting a response.

Ogunsaya’s focus switched to a more attainable goal: an honors African-American history class, right here at OPRF. He sent out a Google Form to assess interest. He met with the executive membership of the history club. Finally, he reached out to the head of the history department head, Amy Hill.

Hill has worked in education for 20 years, but she’s only headed the history division for two. In this role, she supervises curriculum development, administrative duties, and dozens of teachers.

Over the past two decades, she’s watched the history curriculum grow increasingly inclusive. The United States history curriculum, in particular, has been infused with questions about race and gender, equity and inequity. The world history curriculum has attempted to remove bias, to move away from the prototypical Eurocentrism. There are now two sections each of modern Middle Eastern history, non-honors African-American history, and women’s history. Also, there are two sections studying the history of hip-hop music, a multidisciplinary class that has appealed to students from a diverse array of backgrounds.

What exactly is an honors history class? There isn’t a litmus test for an honors classes, Hill explained. Readings are generally longer, and the pace is typically faster. Though that too is subjective — rigor varies. Qualification for honors and AP classes used to be up to recommendations and test scores. Now, the decision is up to families.

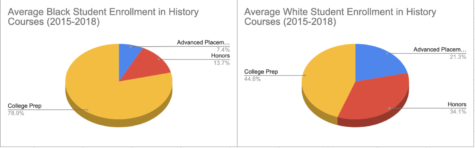

There is still something missing. For the past three years, Hill has tracked data for semester enrollments in history class levels by race and grade. An average of 55.4 percent of white students have enrolled in AP or Honors history classes. Only 21.1 percent of black students have been enrolled in AP or Honors. The ratio of white to black students is about 8:1, though it’s closing in to about 6:1 in the AP classes. Disparities between other races must also be addressed, but the gaps aren’t nearly as wide.

Hill thinks de-tracking will help. She wants to make freshman year a ‘gateway experience.’ Her hope is that students will move onward equally prepared for the rigor of honors classes. She is positive, hopeful, and enthusiastic, so when Ogunsaya approached her, she was excited.

Unbeknownst to Ogunsaya, the idea of an honors African-American history class wasn’t totally unique.

Two years ago, history teacher Tyrone Williams was approached to run a dual credit African-American history class by the former history division head. “Very little progress has been made,” he said. “Only recently been brought back into the conversation.”

Williams had reached out to Illinois Wesleyan University, a private liberal arts college; Indiana Wesleyan University, a Christian liberal arts college; and Loyola University, a Catholic research university. These institutions, he said, have been dragging their feet, and are difficult to communicate with.

He teaches the current African-American history class. “The curriculum varies from year to year,” he explained. In the beginning of the semester, Williams assesses the group’s prior knowledge, and goes from there. They start the class on the continent of Africa, pre-European contact, and travel up to the present.

The curriculum of African-American history is meant to be “inviting for all learners,” so standardization, which is what an AP curriculum would do, would hurt the inclusivity it currently maintains. And though it is a challenging class with a compelling subject matter, at times painful, at other times deeply beautiful; it isn’t and won’t be classified as honors.

What will become of the central, unanswerable question — the achievement gap that OPRF is reckoning with, the same one exposed by “America to Me”? Every summer, Williams works on the AP Bridge class, which prepares students to take AP classes. They do a lot of local history, he said. They work on things like in-class discussions and essays. He gathers with anywhere from eight to forty students. The students, Williams said, almost universally go on to do very well, regardless of if they choose honors or non-AP options.

Ogunsaya’s honors African-American history course isn’t fleshed out. Neither is Williams’ proposal. This year, Hill, Williams, and Ogunsaya hope to collaborate, to reach some kind of arrangement. Beyond accepting Ogunsaya’s proposal or moving forward with Williams’, an option would be to amend the current course and add “opt-in honors,” which means to include a project of some kind that, if passed, would add an honors designation to the transcript. Whatever shape it might take, an advanced honors African-American history class will likely soon come to fruition.