In 1959, a former Schutzstaffel guard who worked at Gross Rosen concentration camp, Reinhold Kulle, was hired as a custodian at Oak Park and River Forest High School. In 1983, when his identity was revealed, the community rallied behind him by defending his right to continue to work at the school, and staff testified to his character.

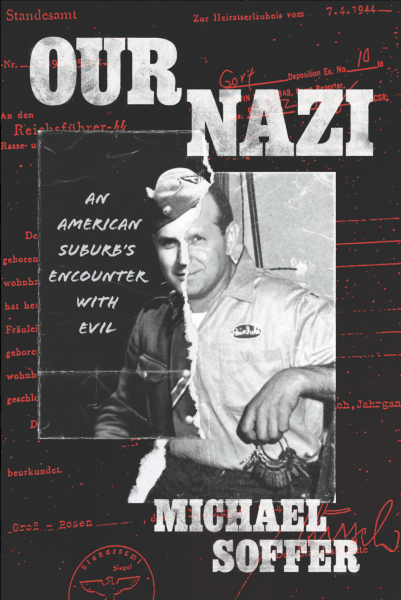

OPRF history teacher Michael Soffer tells the tale in his upcoming book “Our Nazi: An American Suburb’s Encounter with Evil,” which will be published by the University of Chicago Press in September.

Though the events it recounts took place more than 40 years ago, they raise questions about a community that then and now prides itself on being progressive.

The book is the culmination of years of research. “I did not set out to write a book,” said Soffer. He presented his inaugural 2020 Holocaust Studies students with the historical event and continued to research as they asked him more questions.

Holocaust Studies, a one

semester elective, was created by Soffer in 2018 “in response to the wave of antisemitic hate crimes at OPRF,” he said.

In 2018, “antisemitic symbols were sent around during a large assembly; antisemitic and racist graffiti was found in bathrooms; and racist graffiti was found on the softball shed,” according to a 2022 Trapeze article, which noted a similar incident that took place in May 2022.

History Division head Amy Hill talked about the importance of having a Holocaust Studies class in a time where “there’s an increase in antisemitic violence in the United States and around the world. Some people deny the existence of the Holocaust.”

Talia Black, a senior at OPRF and a Senior Instructional Leadership Corp (SILC) for Soffer’s Holocaust Studies class, explained, “I think learning about the Holocaust, and Jewish history in general, is integral into becoming [a]…more understanding person.”

Hill said the “overarching goal of [the class] was obviously for kids to learn more in depth about the Holocaust, but as a means for developing empathy for modern day injustice.”

Along with his students, Soffer “looked through old Wednesday Journals and old Oak Leaves looking for names. We made a list of people who had been around then, and I said I would start calling and emailing, and I just kind of cold called and emailed people and explained, ‘Hey, we’re this class, and we’re interested in the story. Would you talk?’”

Even after the class ended and the spring semester began, Soffer said he “became obsessed and fascinated.”

After time spent researching and writing, Soffer eventually sent a book proposal to his alma mater, Brandeis University. After being turned down, he tried the University of Chicago, the “most prestigious press I can think of,” he said, figuring “when they say no, they’ll maybe give me some good advice, and I can move forward.”

But the University of Chicago Press did not say no. In fact, an editor there “was really interested, and it kind of went quickly from there. I sent some sample chapters that I had written, they were interested, they asked for the first half of the book, they sent it out for peer review, the reviewers came back positive, and we signed a contract shortly thereafter,” said Soffer.

“I realized that there were a lot of books about how Nazis had gotten into the United States, and there were a lot of books about how they had gotten caught. But what I was interested in was what had happened when they got caught in their local community, and there didn’t seem to be anything about that.”

Soffer, who grew up in River Forest, explained that while some community members were aware of Kulle’s hiring, it was “always described as this weird quirk that we had had a Nazi who had worked here. And I always found it incredibly disturbing, not just that he worked here, but that we described it as a quirk.”

Not every community member supported Kulle. Specifically, Soffer named Rae Lynne Toperoff and Rima Lunin Shultz as two women who “really pushed to have Kulle removed.”

“These two women worked tirelessly, just on the power of moral suasion, to try and have their community do the right thing,” said Soffer. “They were vilified by this community. They were threatened. They were denounced. They were called McCarthyist. They were called Stalinist. They were compared to Hitler, for wanting a Nazi to stop working in a diverse public high school.” Soffer is “excited for that story to finally be told differently.”

Hill urged “everybody” to read Soffer’s book. “This is our history. You know, it’s absolutely important.”

Black agreed, saying “it’s crazy how it connects to my own community…It definitely put a lot of things into perspective.”

With the creation of his Holocaust Studies course and the upcoming publication of his book, Soffer is “becoming a leader in Holocaust education around the country,” said Hill. His book is “an achievement that stands out among all of his colleagues and reflects his passion, hard work and care for future generations to know the story of not just Reinhold Kulle but of other Nazis in the United States.”