All Oak Parkers know that constant sound: the endless hiss of cars sliding through the gaping Eisenhower Expressway trench, a river of noise we’ve learned to ignore. We pride ourselves on being a diverse mosaic of people and stories, but there’s one thing that unites us all: the shared misery of traffic on I-290. What we don’t share, or even think about, is the loss buried beneath it. That highway wasn’t always there. Once, it was a community — erased for false promises of convenience and speed.

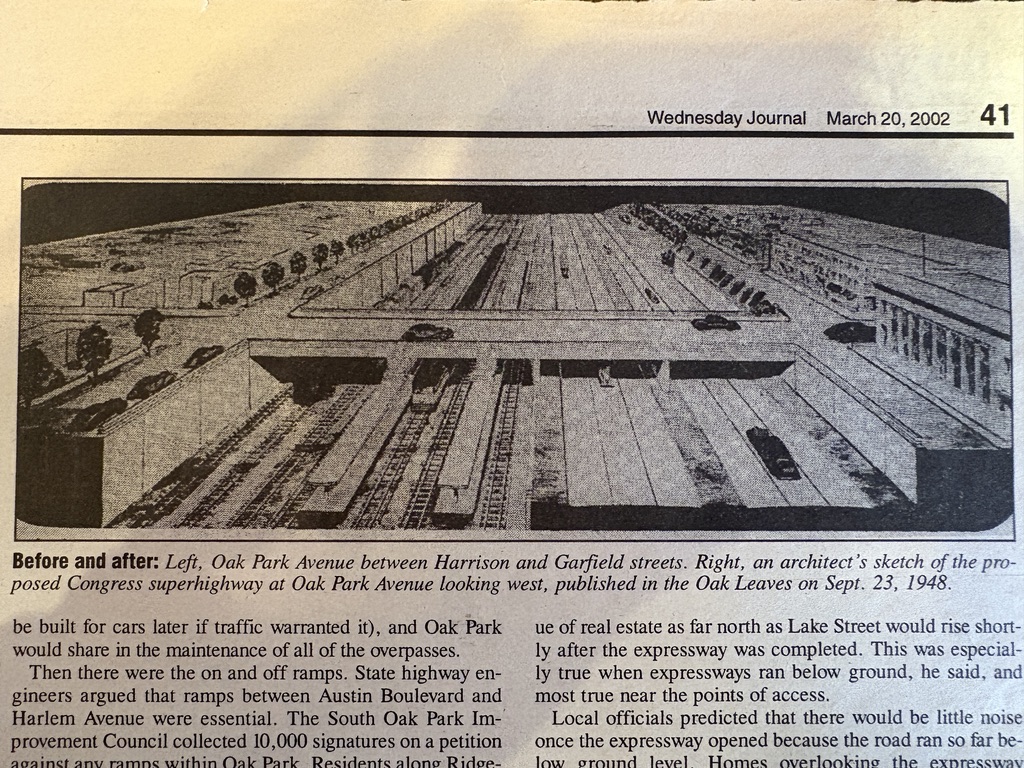

The idea of carving a highway straight through Chicago’s West Side started as a dream in Daniel Burnham’s 1909 plan for the city, long before anyone knew what it would destroy. For decades, the idea sat in drawers and meeting rooms, waiting for someone in power to make it real.

That someone came in 1940, when Cook County gave it the green light. The planned “Superhighway” was to run from just outside the loop straight west to the Cook County line down Congress Street, slicing straight through densely populated Oak Park. Like so many “modern” projects of its era, the Superhighway didn’t care what stood in its way. Blocks of family homes, mom-and-pop shops and tree lined sidewalks were leveled for what planners called progress. Neighbors called it a pit.

Oak Park was no exception. When construction began in 1955, the wrecking crews came first, razing 74 homes and 37 apartment buildings in Oak Park alone, and displacing roughly 2oo families. The state called it compensation. The families called it an insult, payouts that barely covered the cost of a move, let alone a new life.

“It was five years of hell to put it bluntly… five whole years of construction,” said longtime community member Peggy Studney on the construction of the interstate, in a 1995 interview with 7th grade students at Ascension unearthed by the Oak Park Historical Society.

Studney lived directly next to the expressway from before its construction until her death in 2010. The houses directly adjacent to hers were cleared for highway construction. “When you’d look out the window, you’d see nothing but mud when it was rainy and nothing but dry dust when it was dry,” she said. “And there was a huge ditch there unprotected. I don’t know how deep it was, but it was a very deep ditch. And all the rest of it from here to where the ditch started was mud, no sidewalk, no road, nothing but mud and heavy equipment. You know, the bulldozers, the cranes. All the heavy equipment is used to park right on our front lawn. So it was not pleasant living through that.”

In typical Oak Park fashion, our community didn’t just roll over for the wrecking crews; we pushed back from the moment the blueprints hit the local papers. As early as 1942, Village Trustee Theodore Nelson was already digging in his heels, promising to fight the highway “as long as I’ve got a tongue in my head.” That fire didn’t die out. A decade later, when the state tried to carve ramps and overpasses wherever it pleased, Oak Parkers packed meetings, filed petitions, and even talked about seceding the area south of I-290 to Berwyn if it was cut off from the rest of the village.

Some even took their fight to court, like Brack Cox, who was paid a meager $9,420 ($142,000 in 2025) for the demolition of his home. He sued, stood his ground, and won, pushing the state to pay $13,500 ($203,000) instead. In the end, it took years of noise, nerves and negotiations before the state finally agreed to compromise.

By the time the ribbon was cut in 1960 and paraded around for political gain, the price tag for Oak Park’s portion alone had ballooned to $150 million in today’s money ($1.5 billion for the whole expressway).

The Eisenhower was meant to save us the 45 minutes it took to drive to the loop on surface streets. Decades later, it still takes 45 minutes, only now the neighborhoods around the blue line are gone. We traded porches and corner stores for fumes and noise, convinced it was progress. What’s left isn’t speed, just the hum of engines and the ghosts of a community that should have never been lost.

Oak Parkers need to look at that scar cutting though our town and ask what we really gained. I-290 isn’t just a road, it’s a reminder of how easily convenience can bulldoze a community, how progress can leave us stranded in the same traffic we started with. Every time we drive it, every time we hear it rattle by our windows, we should remember what it cost. Because if we forget, we risk letting the next “improvement” take something from us we can’t ever rebuild.