The stats and psychology behind “senioritis”

The phenomenon has been belittled in the media, written about in scientific literature, and become a part of the high school vernacular.

The phenomenon has been belittled in the media, written about in scientific literature, and become a part of the high school vernacular.

But why does senioritis happen? How much does it affect students’ performance, and what can be done to mitigate it?

An informal survey of 38 self-identified OPRF seniors found that on a scale of one to five, 45% of students gave a five, indicating that they have experienced senioritis “very strongly.” Twenty-one percent each gave a three or four, while only 11% gave a two, and 3% gave a one, meaning that they haven’t experienced senioritis at all.

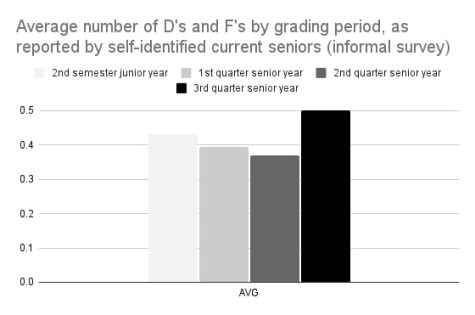

The sample also reported a modest increase in the number of D’s and F’s they have received third quarter as compared to quarters one and two (see chart, right).

“I make fun of senioritis in class, but I actually don’t see as much of it as you’d imagine,” says AP English Literature teacher Bernie Heidkamp. “Maybe that’s partly because it’s an AP class, and we have an exam at the end.”

“I always tell students it’s a college class, they’re already in college. So any kind of senioritis is in the past,” Heidkamp says.

“We try to make sure that our second semester has some really high interest novels and poems,” he says. “We usually begin it with a reading of Shakespeare’s ‘King Lear’, we perform a little bit.”

Heidkamp says that the fact eight semesters of English are required for graduation can complicate things when senioritis strikes. “It’s kind of both my responsibility and the student’s responsibility to make sure we remind each other that” the class is “something we need to get done.” Heidkamp tries to be “lenient,” however, and understands that “there’s a lot going on in (seniors’) lives.”

School psychologist Rachel Megibow says senioritis is caused by multiple factors. “No one’s trying to not graduate when they experience senioritis,” she says. “You’re really transitioning for the first time out of compulsory education” during senior year, Megibow says. “That’s a big transition, which has a lot of impact overall on our motivation (and) on our emotions about school.” This, Megibow says, can lead to “a little bit of self-sabotage.”

Megibow also suggests that seniors may be dealing with burnout. “You all put so much effort into achieving (in school), and that level of stress… takes a toll on the brain.”

Once students get accepted to a college (or have their next step planned out), it’s harder for many students to “maintain the same motivation” since they “know the next step is coming,” she says. “For so many (getting into college has) been the finish line for you since you were in preschool.”

“You perceive you’ve kind of met your goal here, and you’re just kind of finishing your time,” Megibow says. “I think we see this with adults as well. When adults are getting ready to leave a job or they’re getting ready to retire, I think they get a little bit of senioritis, too.”

Megibow also points to the brain’s frontal lobe development as an issue. “That’s the part of our brain that helps us make decisions and helps us weigh consequences of things,” she said. The frontal lobe, which is not fully developed until around age 25, also helps with emotional regulation and delayed gratification. “If you’re looking for that ability to push through a little bit of boredom to get something done, that’s very much a frontal lobe function,” Megibow said.

Laurie Fiorenza, assistant superintendent for student learning, says that while “there aren’t specific services and supports for just seniors,” the school uses “a multi-tiered system of support that monitors all students.”

“When we see students are struggling, the PSS teams really sit down and have conversations about all of the data points and look for what could be the root cause of the struggle for seniors and then recommend appropriate supports.” Supports include the tutoring center, help with executive functioning, and social-emotional support.

“We also have in-school credit recovery if we see that our seniors are slipping in the necessary credits for graduation,” Fiorenza says. “We monitor (the data) all year for all students and put in those systems and services as we see the need.”

Heidkamp emphasizes that while senior year is not the time to slack off, “I always tell them that this is a time to stop and smell the roses. It’s time to be a little bit adventurous and do something memorable.”